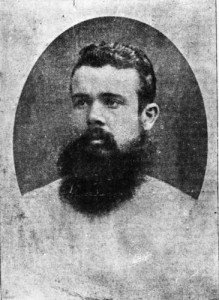

Portrait of Christie Palmerston, State Library of Queensland http://hdl.handle.net/10462/deriv/58144

Author: Russell McGregor

Collector: Christie Palmerston

Born: circa 1850, possibly in Melbourne

Died: 15 January 1897 in Kuala Pilah, Malaya

Active: Palmerston was in the Queensland Wet Tropics from 1874 to 1888

Background biography: Nothing is reliably known of Christie Palmerston’s origins and upbringing. Palmerston himself seems to have wanted to keep things that way. He may have been a son of the Italian Count Gerolamo Carandini and his operatic diva wife, Marie. Or maybe not. Perhaps he was born in Melbourne. Or it may have been Adelaide or Hobart. Birth-dates provided by Palmerston himself range between 7 April 1848 and 23 September 1852. Probably he was of illegitimate birth, perhaps an orphan or foundling.

Information on Palmerston becomes less hazy from the time he began coming under official notice. In February 1869 he was charged in Rockhampton with horse-stealing, and on 6 April that year he was admitted to gaol on St Helena Island in Moreton Bay. Released in November 1870, within eighteen months he was on the Etheridge gold field and on the Palmer field by 1873. Thus began a sixteen-year career as prospector, explorer and entrepreneur in North Queensland.

Palmerston conducted some forays around the fringes of the rainforest in the latter part of the 1870s, but it was in the next decade that he won fame as a jungle explorer – indeed, as the jungle explorer. In this enterprise, he was not averse to self-promotion, often signing his name ‘Christie Palmerston Explorer’ and giving his profession, in court and in the marriage register, as ‘Explorer’. He published long, detailed accounts of his jungle adventures in the Queenslander and other newspapers, and seems to have relished the public acclaim earned from these episodes. By navigating through dense jungle and living there for months on end, Palmerston became something of a legend in his own lifetime, in the admittedly rather small European community living in North Queensland in the late nineteenth century.

Palmerston collected some ethnographic artefacts but he was neither an avid nor a systematic collector. His contributions to material culture studies of the Wet Tropics derive, rather, from his extensive travels with and among rainforest Aboriginal people and the observations he made on their manner of living. He was one of very few Europeans to subsist for extended periods on a rainforest Aboriginal diet, and he left detailed descriptions of how seeds, nuts and other vegetable foods were ground, leached and otherwise processed before consumption. Referring to North Queensland’s rainforests, he remarked on ‘the abundance and variety of good food these jungles contain’, but added, tellingly, ‘flesh excepted’. Like several other nineteenth-century observers, Palmerston suggested that a scarcity of game in the rainforest impelled its inhabitants into cannibalism.

Palmerston made observations on the manufacture of rainforest weapons, including the long hardwood swords and huge softwood shields distinction to the region. ‘Each tribe has a different design on the face of its shields’, he claimed, and the designs were painted partly with human blood obtained by the artist poking a sharp object up his nose. He explained how rainforest groups maintained small patches of open land (‘pockets’) within the jungles, on which they erected clusters of large, thatch-roofed huts which comprised, in effect, semi-permanent villages. He remarked on the numerous wide paths that connected these ‘pockets’, and often used these paths for his own travels.

Although Palmerston made some close observations of rainforest Aboriginal people, he was not a particularly sympathetic observer. He held several Aboriginal individuals in high regard, but freely expressed his contempt for Aboriginal people in general (and for Chinese and other non-white people as well). At the time he conducted his rainforest explorations, most of North Queensland was in a rough and raw phase of frontier expansion. Inter-racial violence was commonplace, but Palmerston seems to have been exceptionally quick to resort to the rifle, even by contemporary standards. His accounts of his jungle explorations are littered with incidents involving bloodshed, far more than most contemporaneous accounts by travellers in the region.

Palmerston made his name as an explorer of the North Queensland rainforests and as the possessor of unparalleled skills of bushmanship in this environment. Yet in his accounts, the hardships of living in the damp, dank rainforests are palpable. Constantly, he was plagued with leeches, ticks, mites and other pests; frequently he fell victim to fevers during which he would lie shivering and sweating in the mud and teeming rain. He often travelled almost – or perhaps entirely – naked in the rainforest, which must have been a painful experience since he remarked on his frequent brushes with the stinging tree, Dendrocnide moroides.

Palmerston seems to have been addicted to action and adventure. He married Theresa Rooney in Townsville in December 1886, and shortly afterward made an apparent attempt at domesticity by adopting the (relatively) settled life of a publican in that town. But in 1890 he departed for Borneo, then Malaya, leaving his wife and infant daughter, Rosina, in Townsville. In Malaya, he continued exploring and prospecting in the rainforest, accompanied by local indigenous people. There he died after suffering another bout of fever.

Sources: G. C. Bolton, ‘Palmerston, Christie (1850–1897)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/palmerston-christie-4361/text7089

Paul Savage, Christie Palmerston, Explorer, Townsville, Department of History and Politics, James Cook University, 2nd edn, 1992.

F.P. Woolston and F.S. Colliver, ‘Christie Palmerston—a North Queensland pioneer, prospector and explorer’, Queensland Heritage, vol.1, no.7, 1967, pp.30-34